|

|||

| Copyright © (text only) 2000 - Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

- This essay appeared originally in

What is

Art?...What is an Artist? (1997)

4. Modernism & Postmodernism In the later half of the 20th

century there has been mounting evidence of

the failure of the Modernist enterprise. Progressive modernism is riddled

with doubt about the continued viability of the notion of progress.

Conservative modernism, in the United States at least, has fallen prey in

the political realm to the influences of the Church in the form of the

so-called religious right which in recent years especially has seriously

undermined the very constitutional foundations of the whole American

experiment.

Since Suzi Gablik wrote her book, the communist experiment undertaken

in the former Soviet Union has collapsed. Fundamentalism in nearly all of

the world's major organized religions (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism) has

risen sharply in recent years in direct opposition to modernism. American

Christian fundamentalists still agree with Martin Luther who recognized

that "Reason is the greatest enemy that faith has; it struggles against

the divine word, treating with contempt all that emanates from God."

A growing number of people believe the modernist enterprise has failed.

In the search for reasons to explain this failure, questions have

necessarily been raised about the whole Western humanist tradition.

It has become apparent to many that the worldview fostered through

Modernism (and by the Western humanist tradition) is flawed, corrupt, and

oppressive. Both recent events (i.e. since the World War Two), and the

perception of those events, have given rise to the notion that Modernism

has played itself out and is now floundering and directionless.

If Modernism is at an end, we are now facing a new period. The name

given this new period is Postmodernism.

The term postmodernism is used in a confusing variety of ways. For some

it means anti-modern; for others it means the revision of modernist

premises.

The seemingly anti-modern stance involves a basic rejection of the

tenets of Modernism; that is to say, a rejection of the doctrine of the

supremacy of reason, the notion of truth, the belief in the perfectability

of man, and the idea that we could create a better, if not perfect,

society. This view has been termed deconstructive postmodernism.

An alternative understanding, which seeks to revise the premises of

Modernism, has been termed constructive postmodernism.

Deconstructive postmodernism seeks to overcome the modern worldview,

and the assumptions that sustain it, through what appears to be an

anti-worldview. It "deconstructs" the ideas and values of Modernism to

reveal what composes them and shows that such modernist ideas as

"equality" and "liberty" are not "natural" to humankind or "true" to human

nature but are ideals, intellectual constructions.

This process of taking apart or "unpacking" the modernist worldview

reveals its constituent parts and lays bare fundamental assumptions.

Questions are then frequently raised about who was responsible for these

constructions, and their motives. Who does modernism serve?

From the history outlined is this essay, it should be clear that

modernist culture is Western in its orientation, capitalist in its

determining economic tendency, bourgeois in its class character, white in

its racial complexion, and masculine in its dominant gender.

Deconstructive postmodernism is seen perhaps as anti-modern in that it

seems to destroy or eliminate the ingredients that are believed necessary

for a worldview, such as God, self, purpose, meaning, a real world, and

truth. (This point of view, though, that we need a worldview comprised of

notions of God, self, purpose, etc, is itself a modernist one.)

Deconstructive postmodern thought is seen by some as nihilistic, (i.e.

the view that all values are baseless, that nothing is knowable or can be

communicated, and that life itself is meaningless).

Constructive postmodernism does not reject Modernism, but seeks to

revise its premises and traditional concepts. Like deconstructive

postmodernism, it attempts to erase all boundaries, to undermine

legitimacy, and to dislodge the logic of the modernist state. Constructive

postmodernism claims to offer a new unity of scientific, ethical,

aesthetic, and religious intuitions. It rejects not science as such, but

only that scientific approach in which only the data of the modern natural

sciences are allowed to contribute to the construction of our worldview.

Constructive postmodernism desires a return to premodern notions of

divinely wrought reality, of cosmic meaning, and an enchanted nature. It

also wishes to include an acceptance of nonsensory perception.

Constructive postmodernism seeks to recover truths and values from

various forms of premodern thought and practice. Constructive

postmodernism wants to replace modernism and modernity, which it sees as

threatening the very survival of life on the planet.

Aspects of constructive postmodernism will appear similar to what is

also called "New Age" thinking. The possibility that mankind is standing

on the threshold of a new age informs much postmodernist thought.

The postmodern is deliberately elusive as a concept, avoiding as much

as possible the modernist desire to classify and thereby delimit, bound,

and confine. Postmodernism partakes of uncertainty, insecurity, doubt, and

accepts ambiguity. Whereas Modernism seeks closure in form and is

concerned with conclusions, postmodernism is open, unbounded, and

concerned with process and "becoming."

The post-modern artist is "reflexive" in that he/she is self-aware and

consciously involved in a process of thinking about him/herself and

society in a deconstructive manner, "demasking" pretensions, becoming

aware of his/her cultural self in history, and accelerating the process of

self-consciousness.

This sort of sensitivity to cultural, ethnic, and human conditions and

experiences has been ridiculed by conservatives in recent years as

"political correctness."

What about art? It could be argued that several forms of art have been

"post-modern" since the First World War. If the mass slaughter of the

Great War, achieved through the advances made in science and technology,

was the result of the modernist commitment to "progress," then one might

begin question the value of the modernist enterprise.

Nonetheless, between the wars, progressive modernism managed to sustain

a vision of a better future. It continued to see tradition and the past as

stifling the expression of freedom. The Surrealists before the war still

clung to the modernist belief that their art could influence human

destiny, that they could change the world.

After the Second World War, however, such optimism in the future was

difficult to sustain. And to make things worse, with the advent of the

Cold War and the constant threat of nuclear destruction, any sort of

future looked doubtful.

Having rejected the past many years ago, and now with the future no

longer the goal of artistic effort, many artists turned with visible

distress to the present and focused their attention on contemporary

popular culture.

Popular culture, however, was undergoing a tumultuous upheaval during

the sixties: the Civil Rights movement, opposition to the Vietnam war, the

emergence of a widespread women's movement, and the transformation of

hitherto largely passive and conservative students into the cutting-edge

of opposition.

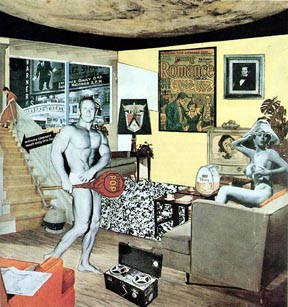

Pop artist could still appear progressive under these circumstances,

contributing a critique of bourgeois ideals and the American dream (for

example, Richard Hamilton).

Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today's Home So Different, So Appealing? 1956, Collage (Kunsthalle Museum, Tübingen, Germany) What was happening in effect, though, was that modernist art itself was under attack as a bourgeois ideal; a sort of nihilistic neo-Dada which I would identify as Postmodern.

Chris Witcombe | Sweet Briar College |